If you’re a new boat owner or you need a refresher on the right-of-way rules for boating — this article is for you.

While we all love to have fun on the water, safety is always the priority. You may be intimidated thinking about driving your new boat down a crowded waterway with all different types of vessels crossing your path. How does everyone know where to go and how to stay out of each other’s way? Fortunately, there are regulations to minimize collisions and to maintain order and safety. However, it is also important to note that despite the rules, it is always your responsibility to avoid a collision, no matter the scenario.

Every good captain must know how to approach interactions with other boats — just like how it’s essential to know traffic rules when driving a car. When you understand the fundamental boating right-of-way rules for rivers, oceans and harbors, you can easily cruise through the most crowded waterways. Let’s dive in.

The Importance of Knowing Boating Right-of-Way Rules

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) reported that 75% of boating fatalities were caused by vessels operated by people who didn’t have boating safety training. Most reported accidents involved personal watercraft (PWCs), open motorboats and cabin motorboats.

Surprisingly, most recreational boaters aren’t familiar with boat right-of-way rules, which causes confusion and makes their boating experience less safe and more stressful. If you master even the basic principles of boat-passing rules, you’ll know how to behave in any situation and keep your cool.

As the captain of your vessel, it’s your responsibility to maintain the safety of your boat and everyone onboard. The more knowledgeable you are about how to do that — such as knowing and understanding boating right-of-way rules and collision regulations — the less you have to worry about something going wrong.

First things first — a few general tips and boating rules for maintaining navigational safety:

Don’t Speed

If you can increase the overall safety of your vessel or a vessel nearby by slowing down, you should. Sometimes the conditions are right to go fast, and sometimes they aren’t. It’s the job of a good skipper to know the difference. Take into account how many other boats are around you and if you have the proper space to slow down quickly.

Avoid All Government Vessels and Restricted Areas

These vessels and areas almost always have the right-of-way, so it’s best to give them plenty of space.

Be Cautious of Other Boaters

Just like when you’re driving a car, just because the rules of the road exist, it doesn’t mean everyone follows them. Some recreational boaters may not follow the rules. If their actions seem unsafe, keep enough distance between you and them so that any unexpected maneuver won’t catch you off guard.

Be Respectful and Conscientious

While sometimes you may be operating under legal conditions, it is still nice to give other boaters the respect and the space they deserve. Just because you have the right-of-way doesn’t mean you have to take it every time.

Give Way When It Makes Sense

Even if you have the right-of-way in a situation that could be dangerous, it’s your responsibility to alter your course if it means avoiding an accident. If you did not change your course and an accident occurred, you could still be at fault even if you did have the right-of-way. Safety always takes precedence.

Rules for Typical Boating Scenarios

How two boats approach each other determines which has the right-of-way. Position, direction and the different levels of priority for different vessels make up the majority of the rules on the water. We’ll get into the different types of vessel priority a little later.

When a vessel has the right-of-way, they’re called the “stand-on” or “burdened” vessel. If you’re the stand-on vessel, you must confirm the give-way vessel’s actions by maintaining your course and speed until you pass them or need to alter your course.

The “stand-off” or “give-way” vessel is the one that doesn’t have the right-of-way.

What does it mean to give another vessel right-of-way? You must ensure they can hold their current course and speed, which may mean substantially altering your course in a way that’s clear to the stand-on vessel.

For this article, we’re assuming you operate a power-driven vessel — the rules are a little more complicated if you’re sailing.

Here are some common scenarios you’re likely to encounter on the water:

1. Facing a Non-Power Vessel

When you’re approaching a vessel without motor power, such as a sailboat, they have the right-of-way.

An important note is that a sailboat must be using sail power only, also known as “under sail,” for it to have the right-of-way over power-driven vessels. If it’s using a small outboard motor, the captain has equal right-of-way as a typical powerboat.

In recent years, we have seen a proliferation of human-powered craft, such as kayaks and paddleboards. The USCG Navigation Rules refer to human-powered craft as “vessels under oars” and they are singled out only in the lighting rules. Otherwise, they are simply “vessels.”

We may encounter these vessels in three different navigational situations. We may encounter them in overtaking situations. The vessel being overtaken is the most privileged vessel on the high seas. The two other navigational situations in which we may encounter paddlers are head-on and crossing situations.

Interestingly, the rules don’t make specific provisions for power-driven vessels encountering vessels under oars in head-on and crossing scenarios. Rule 2 is the “responsibility” rule and it, in essence, tells us to use good judgment based on the whole of the navigational picture. In head-on situations, the standard port-to-port passing should serve us well. In crossing situations, there’s no reason why we can’t apply the rules of power-driven vessels as well. The boat with the other to its starboard (right) shall give way.

In short, Rule 8 tells us we must take all reasonable action to avoid a collision. Vessels under oars move relatively slowly and are easy to avoid. When encountering them, take early and positive action to pass at a safe distance. In any case of uncertainty, the rules reveal when to slacken the speed.

2. Facing Power-Driven Vessels

When two boats have the same priority of right of way based on their classification, the determining factors become position and direction of travel.

To determine the position of another vessel relative to your own, you must know the nautical terms to refer to different “sectors” of your boat, i.e., starboard, port and stern. Once you identify where another boat is relative to your own, you’ll know who has the right-of-way.

Using the following simple rules, you’ll have a good grasp of how to navigate around other powerboats:

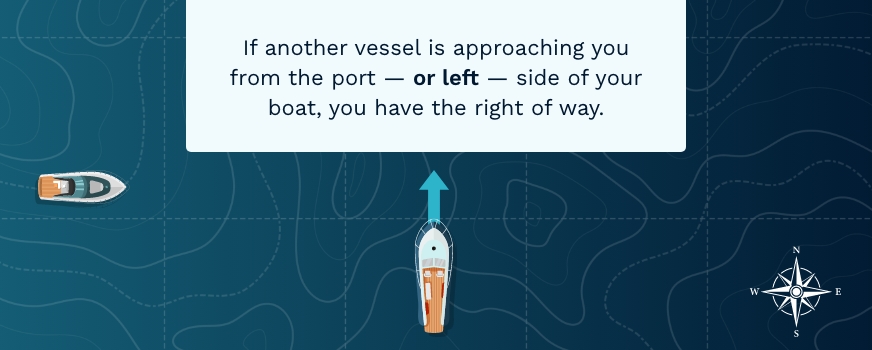

1. If another vessel approaches you from the port (left) side, you have the right-of-way and should maintain your speed and course.

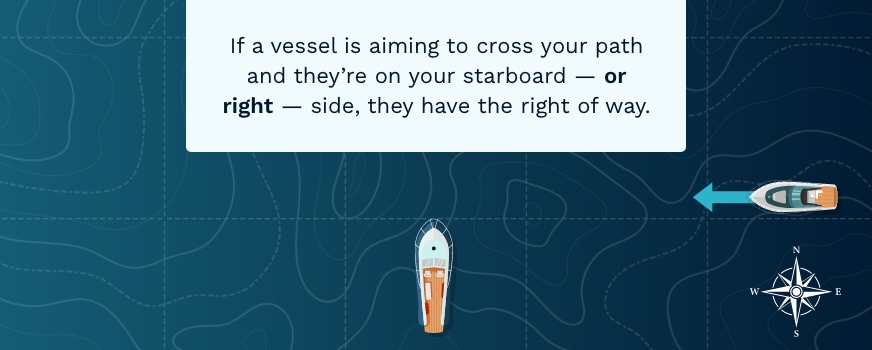

2. If a vessel aims to cross your path and they’re on your starboard (right) side, they have the right-of-way. Alter your course so that you will pass them at a safe distance and in a way that is apparent to the other skipper.

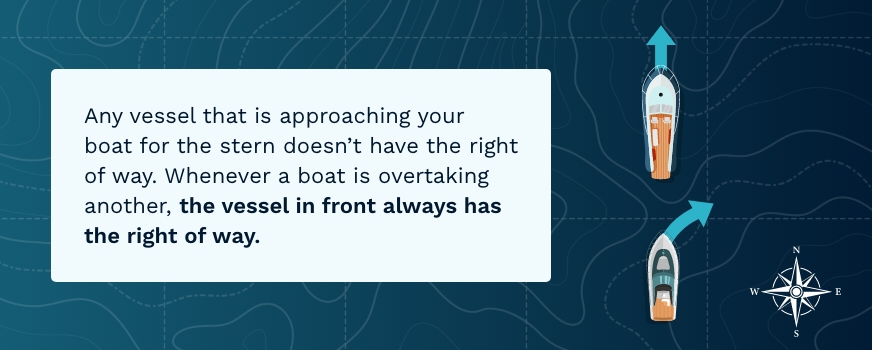

3. Any vessel approaching your boat from the stern doesn’t have the right-of-way. Maintain your speed and course. Whenever a boat overtakes another, the vessel in front always has the right-of-way and should be allowed to continue its original course unhindered. This is the case even if the vessel behind has a higher level of right-of-way priority, such as a sailboat.

When the evening approaches and boaters turn on their navigational lights, there’s an easy way to remember who has the right-of-way:

- When you see a red navigational light on another boat, it indicates their port side and that they have the right-of-way.

- When you see a green navigational light, you’re approaching a boat from its starboard side. You have the right-of-way.

- How do you know if you’re overtaking another vessel at night? Look for their white stern light and steer clear. The stern light shines at 22.5 degrees on either side of the boat behind the widest point — the beam.

Knowing the basics listed above will have you in great shape in most boating situations. Below are some of the best practices that will help take your navigational skills to the next level:

If You’re Passing through a Crowded Harbor

One of the best tips for this scenario is to always aim for the stern of a boat you want to go behind — this lets the other boat operator know that you intend to go behind them and they can continue their course. Captains will sometimes use a VHF radio to communicate their intention to “take the stern” of another boat as a courtesy and to keep traffic flowing more smoothly.

If You Meet Another Boat Head-on

Under the boating rules of the road, vessels approaching each other head-on are always supposed to pass each other port to port — or left to left, just like on the road. However, crowded harbors and times when many boats come together at once make this difficult to follow all the time — stick to the rules as much as possible, but use your best judgment to keep everyone safe.

If You Want to Use a Horn to Communicate or You Hear Another Vessel’s Horn

Experienced skippers will sometimes use their horns to communicate. Here are some of the sound signals that boaters use to communicate with others:

- One short blast: This signal typically means the boater is changing course to starboard.

- One long blast: Typically, large motorized boats give this signal to communicate that they are leaving the dock.

- Two short blasts: The boater is changing course to the port.

- Three short blasts: This signal is usually a warning that the boat is reversing.

- Five quick blasts: If you hear this, the passing may be unsafe or the boater who gave the signal may be uncertain of another boater’s intentions. In this situation, avoid passing the vessel.

Please keep in mind that international rules can differ.

If You’re on a “Collision Course” With Another Vessel

Remember, you must alter your course with ample time to safely avoid a collision, even if you are the stand-on vessel. The definition of a “collision course” is when the bearing from one boat to another isn’t changing, while the distance between your two boats is shrinking.

Once you’re familiar with the basic rules of the road, use them with your best judgment and navigating through boat traffic will be a breeze.

What to Do When Crossing Paths While Boating

Understanding the rules for crossing paths is crucial to help you stay safe on the water. Every boater should know their obligations in any given situation. Here are the rules for crossing paths you should know before heading onto the water:

When Crossing Paths, What Is a Give-Way Vessel’s Responsibility?

The give-way vessel must take immediate action to stay out of the way of other vehicles. It’s the captain’s responsibility to navigate crossing paths by adopting a proactive approach. They must assess the situation, alter the speed or course, or communicate with appropriate signals. It’s also their responsibility to show clear intent in advance, especially if they plan to change course.

The two key responsibilities of the give-way vessel when crossing paths are to slow down or change course. If neither action is taken, there is a high potential for a collision. The stand-on vessel doesn’t need to make any changes like slowing down or switching courses. It’s up to the captain of the give-way vessel to act accordingly to prevent collisions. They must yield to the other boat. Here are the standard ways captains on give-way vessels communicate their intentions to fulfill their responsibility:

- Standardized sound signals

- Visual signals

- Seaspeak via radio transmissions

What Do You Do When You Are Crossing Paths With Another Power Vessel?

In this scenario, the right action depends on whether you are in the give-way vessel or stand-on vessel. If you are steering the give-way vessel when crossing paths, it’s your responsibility to give the stand-on vessel the right-of-way. Communicate your intentions and then maneuver your boat around the stand-on vessel. If you are steering the stand-in vessel, then you must acknowledge the actions of the give-way vessel. Maintain your current course and speed so the other boat can safely maneuver around you.

Who has the right-of-way between vessels if there are two power-driven vessels at a crossing? The vessel with the other power boat on its starboard side is considered the give-way vessel and must stay out of the way. The other power vessel is considered the stand-on vessel, and the captain will continue with the route and maintain its speed.

The rules at night also differ. If you see a red light crossing from right to left before you, then your boat is the give-way vessel. If you see a green light, then your vessel is the stand-on and should not change course or speed.

Port Approach

If a powered vessel approaches you from the port (left) side, you are the stand-on craft. This means you have right-of-way, so you can continue in the same direction at the same speed. Stay alert and be ready to adjust as needed.

If you are approaching another vessel from the port (left) side, you are the give-way craft. This means you have to act fast to avoid a collision by slowing down and altering course.

Starboard Approach

If a powered vessel approaches you from the starboard (right) side, they have the right-of-way.

You are the give-way craft. This means you do not have right-of-way. Take immediate action to avoid a collision by slowing down and altering course.

If you are approaching another vessel from the starboard (right) side, you are the stand-on craft. This means you have right-of-way, so you can continue in the same direction at the same speed. Stay alert and be ready to adjust as needed.

If you are the stand-on vessel and you observe that the give-way vessel is not taking appropriate action to avoid collision, you should break the rules and take evasive action.

Overtaking

When one powered vessel overtakes another powered vessel from behind (stern), the approaching boat is the give-way craft and does not have the right-of-way. The boat operator must adjust speed and course to immediately steer to a safe distance from the boat ahead. You are allowed to pass on either the port or starboard side of the vessel, but it is better to pass on the starboard side.

Right-of-Way Between Different Types of Vessels

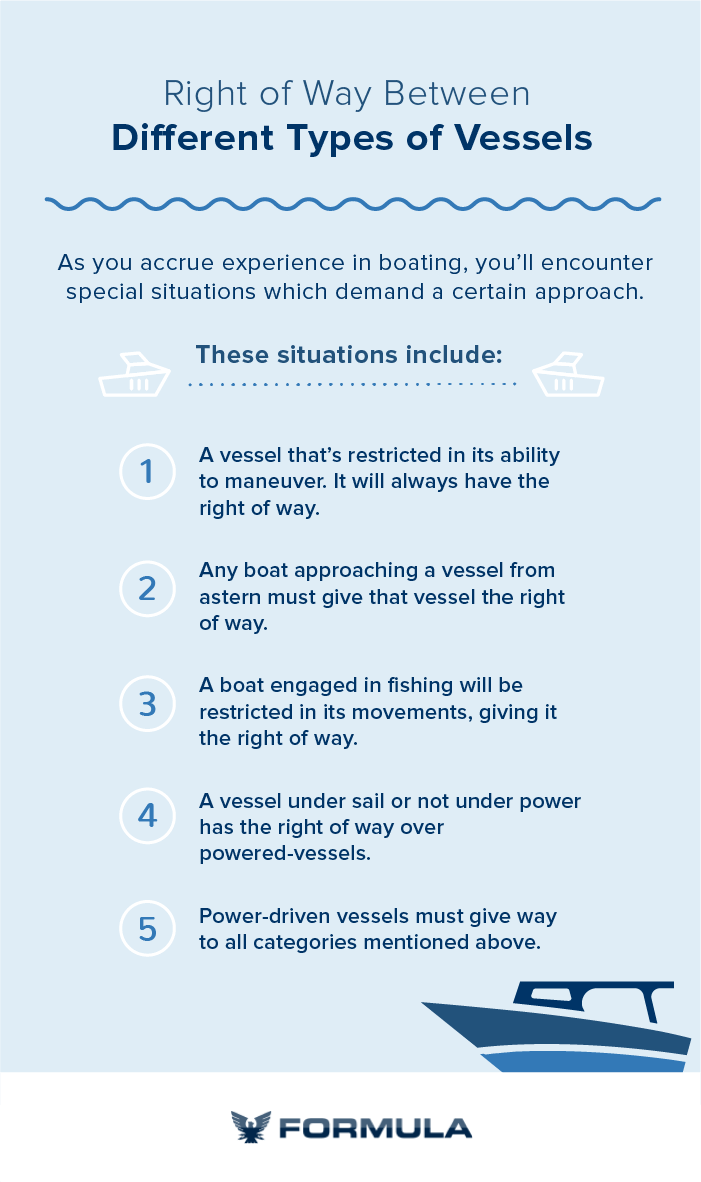

Now that you know the basic rules of the road, we’ll cover a few special situations you may encounter. Besides the basics of power versus non-power boat rules, there’s a pecking order when it comes to the right-of-way — different vessels and conditions determine the stand-on vessel.

Here’s the right-of-way order from the highest level to the lowest:

1. A Vessel Not Under Command or a Vessel Restricted in Its Ability to Maneuver

The USCG gives these two types of vessels the same level of priority. A boat “not under command” means that an unexpected circumstance is keeping the boat from maneuvering, like an engine or steering failure.

A vessel that is restricted in its maneuverability is unable to move out of the way of other boats due to the nature of its work, such as a buoy tender fixing a navigational aid or a vessel transferring passengers while underway.

2. A Vessel Being Overtaken

Any boat approaching a vessel from astern must give them the right-of-way.

3. A Boat Engaged in Fishing

When a power fishing boat has commercial fishing equipment deployed, that restricts its ability to maneuver. Therefore, they have the right-of-way.

4. A Vessel Under Sail or Not Under Power

A vessel under sail, as well as other watercraft that are not powered — such as canoes, kayaks, paddleboards, etc. — have the right-of-way over powered vessels.

5. A Power-Driven Vessel

As a power-driven vessel, you must give way to all the other categories above. If you are converging on another powered boat, either head-on or astern, the right-of-way rules mentioned earlier apply.

A few more unique situations that the USCG doesn’t include on their simplified list are:

- Whenever you hear a siren or see blue flashing lights on an emergency or law-enforcement vessel, give them the right-of-way just like you would an ambulance or a police vehicle.

- Keep an eye out for tugboats and other vessels towing — if in the open ocean, they can have a submerged tow line with a lot of distance between them and their tow.

- Always take the stern of large commercial tankers and container ships in the ocean and never try to cross in front of them.

- Steer clear of docked or moving ferries — some have submerged cable lines. Watch other boats and how they navigate around the ferry before crossing yourself.

- Any boat under 65 feet must steer clear of larger, less maneuverable vessels.

It’s important to maintain a proper lookout at all times when operating your vessel. If your boat is small enough, you may be able to keep track of everything by yourself. If you have a larger boat, you’ll probably want some help from a friend onboard — especially when leaving the dock or landing. Having an extra set of eyes is helpful to any captain, no matter how seasoned.

If you apply these tips and remain alert and responsible when operating your boat, there’s no reason you should get into a collision. If someone who isn’t following the rules happens to bump into you, following the rules only helps your case.

It’s mandatory for any vessel over 39.4 feet in length to carry a copy of the USCG Navigation Rules onboard, but all boats should carry it to stay safe on the water. Be sure to look up your state’s navigational rules before you set out, as they may vary depending on location.

Take Control of the Water With Formula Boats

At Formula Boats, we take safety seriously. As a family company since 1976, we know the importance of protecting your most valuable assets. Owned and operated by lifelong boaters, the Porter family treats every product as a representation of themselves — that’s why we do everything we can to equip our customers with the most reliable boats available.

Our customers keep coming back because when you own a Formula boat — you’re part of the family. If you’ve thought you can’t have it all in a boat, think again. We don’t make boats for the masses — we make premier powerboats for you. With more than 60 years of continued innovation, our precision watercraft surpasses expectations of quality and performance.

Contact us today for any other boating questions you may have or to request a quote.